Today’s post comes to us from personal trainer Micah Faas CSCS. If you do not already know Micah, he is a very bright and talented trainer from Minnesota (which means he is also very polite). Micah is currently working out of Bellevue, Washington. He is an avid sports fan and a sport specific training specialist. If you have any questions for Micah, you can reach him at micahfaas@gmail.com. Enjoy! -Dan

Eccentric training is a method of training that has long been used by body builders, power lifters, and athletes. This article aims to explain why, when, and how to use eccentric training to maximize your athletic performance. First lets cover some basics.

What is eccentric training?

When performing a lift or a movement there are three types of muscle contractions:

Concentric – The muscle is shortening while producing force. This occurs when the force produced by the muscle is greater than the force causing the contraction.

Isometric – The muscle is producing force without changing length. This occurs when the force produced by the muscle is equal to that of the force causing contraction.

Eccentric – The muscle is lengthening while producing force. This occurs when the opposing force is greater than the force produced by contraction.

For example, when performing a bench press the initial movement of lowering the bar to your chest is the eccentric portion. Your muscles are contracting eccentrically while simultaneously lengthening to act like a brake, preventing the bar from dropping on your chest. The brief moment when the bar stops moving as it reaches your chest immediately before you press it back up is the isometric portion of the exercise. As your arms extend and you begin to press the bar the muscle contracts concentrically as the amount of force you are now producing is enough to overcome the weight of the bar.

Eccentric training focuses on the eccentric contraction (muscle lengthening) and your ability to use the kinetic energy stored in your muscles during this contraction to develop more force with the concentric contraction. Incorporating eccentrics into your current training program can have huge benefits for all types of athletic performance.

Why Eccentrics For Athletic Performance?

What separates a good athlete from a great one? When you take skill out of the equation and look at raw athletic ability, what is it that separates the haves from the have-nots? It is the athlete’s ability to produce more force in less time.

Adrian Peterson (child abuse aside) is widely considered to be the best running back in the NFL. Have you ever noticed that Peterson is always running through a lot of arm tackles? Yes he is big and yes he is fast, but so are his opponents trying to tackle him. Size and speed definitely play a roll in his ability to avoid tackles, but that is not what sets him apart. No, what sets him apart is his ability to get defenders attempting to tackle him out of position. Ok, that sounds simple enough but how does he do that? The secret is his ability to decelerate his body quicker than his opponents. When Peterson goes to make a cut so does his defender, but Peterson is able to absorb a greater amount of kinetic energy eccentrically in a shorter duration of time. He then uses that kinetic energy to explode concentrically in the other direction, leaving his opponent out of position behind him and only able to stick his arms out to try to slow him down. The ability to win the battle eccentrically, even by a fraction of a second is the difference between being tackled for a loss and breaking free down the sideline for a touchdown. It is the difference between being able to cross your defender over to create space for a wide-open jumper and having your shot blocked back into your face. It is the difference between you being a good athlete or a great athlete.

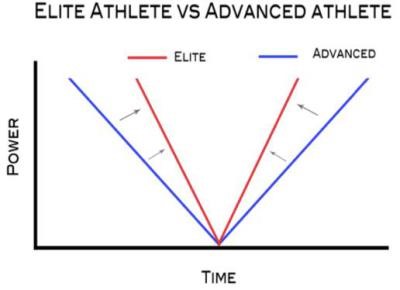

Eccentric training for athletic performance isn’t just about being able to make quick cuts or juke someone out of their socks. Eccentric training allows us to run faster, jump higher, and throw harder. With every athletic movement there is also a counter movement: The squat before a jump, the wind-up before a pitch, the foot plant before you make a cut in the opposite direction. But in order to maximize the movement you have to also be able to minimize the time spent performing the counter-movement and maximize the amount of kinetic energy your muscles can store eccentrically. The chart below, taken from Cal Dietz’s Triphasic Training (2012) illustrates this ability to quickly store and release kinetic energy. Dietz refers to this as winning the “Battle of the V”.

As you can see, being able to generate more force eccentrically in less time results in you also being able to generate more force concentrically in less time. It’s a double whammy. When you win one, you will win the other.

So how do you incorporate eccentric training into your current training program? The first thing to realize is that despite its many benefits, eccentric training is extremely taxing and requires more recovery time than traditional training methods. Furthermore, you should have some previous strength training experience (at least a year) before dabbling with eccentrics. It is also important to note that if you are injured, or recovering from an injury you should avoid eccentric training unless given clearance by your doctor, physical therapist, or strength coach. Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, here are a few different ways you can start using eccentrics to improve your athletic performance.

Plyometric Movements

Yes, plyometric exercises are a form of eccentric training. You are training your muscles to minimize ground contact time by rapidly decelerating, stabilizing, and then exploding concentrically by using the stored kinetic energy (stretch-shortening cycle). You are also training your neuromuscular system through the stretch reflex mechanism. This protective mechanism is activated when the neuromuscular system detects a muscle being stretched and rapidly contracts the muscle to prevent it from overstretching to bring it back to its original length to prevent injury. The stretch reflex mechanism is likely why your hamstrings feel tight despite the fact that they are elongated while sitting, which we all do far too much of. But that is another topic for another day.

Depth jumps and drop jumps are two good exercises to maximize eccentric performance. When performing these, be sure you are landing on a soft surface, grass or rubber mats work well. With depth jumps, you should land as far away from the box as the box is high. So, if you’re standing on a 30-inch box you should land approximately 30 inches away. When executing depth jumps you should use a simple athletic stance position just as you would whenever you jump.

Drop jump performance can vary. You can land in a regular athletic stance for general carryover, in a stiff-legged stance to emphasize lower leg force production ability, in a 1/2 squat to emphasize the hips and hamstrings, in a split squat stance to emphasize all around balance, and in a 1-legged stance to heighten the magnitude of force absorbed. It is important that you are able to absorb the impact and “stick” the landing. If you are unable to land without faltering your box height is too high. Box heights of 24 inches for males and 18 inches for females are a good starting point.

With all plyometric movements it is important to keep the sets short in duration and explosive in nature. Remember; we are training to develop maximal force in minimal time. Once you start getting fatigued your eccentric and concentric movement slows down and you will find yourself pausing briefly at the midpoint of the movement (isometric hold). When this happens you are losing the benefits and your fatigue will make you more prone to injury. You want to keep the movement fast and free flowing. If you don’t want to hesitate midway through your cut or before your jump, don’t train that way. Aim for 60-100 ground contacts or total volume for novice athletes, 100-150 for more advanced athletes.

Tempo Squats

A tempo squat is a squat where each portion of the movement is done for a specified amount of time. An example of this would be a 3 second eccentric downward movement, a 1 second isometric hold at the bottom of the squat, and an explosive concentric return to the top. For workout card purposes I like to write this as “Tempo Squat 3:1:0”, with the zero meaning as quickly and explosively as possible. Tempo squats can be done 1-2 times per week. Be sure to allow at least 2-3 days of recovery time before repeating. These are best done in sets of 5-6 repetitions at 70-80% 1RM.

Advanced lifters can superset tempo squats (try a 5:1:0 tempo), with an exlosive plyometric exercise such as box jumps or power step-ups. Keep the plyometric set small, no more than 10 reps to avoid excessive fatigue.

Heavy Eccentrics (Greater than 1RM)

One of the great things about eccentric training is that it allows you to work at weights above your 1RM, which can lead to greater strength and hypertrophy. In at 5-week study, Tesch et al, (2004) showed that an eccentric training group could increase their strength by 11% and mass by 6% compared to a concentric-only control group. That is pretty significant! Another study (Farthing & Chilibeck, 2003) looking exclusively at hypertrophy showed the exact same thing, eccentric training is more effective for gaining muscle size than traditional resistance training. Higher intensity means greater stress, which means greater adaptation. Your anabolic response from the heavier load will force you to recruit more muscle fibers, which will allow you to move more weight on the concentric portion of the lift.

Unfortunately, due to the high intensity of the load and the risk of injury, lifting above your 1RM should only be done by advanced lifters and with spotters present. When using supramaximal eccentric training you should expect greater post-exercise soreness. However, according to Steven Fleck and William Kraemer’s book Designing Resistance Training Programs (2003), after 1-2 weeks of eccentric training your soreness should not be any greater than from tradition resistance training.

To lift above your 1RM, try one of the following techniques:

Forced Negatives – With this technique, your training partner or spotter applies additional force to the bar during the lowering/eccentric phase only. If you have an experienced spotter or someone you feel confident in, you can ask them to apply more force at the top of the lift where you are stronger, and less at the bottom where you are weaker. The downside to this technique is that the additional force provided is not quantifiable.

Eccentric Only – This method involves the lifter only performing the eccentric portion of the lift. You will need a power rack to do this on your own. Set the safety bar or pin so that it will be at the bottom of your lift. Lower the weight in a controlled manner, aim for 3-7 seconds, until you reach the safety bar. Rest the bar here, get up and unload the bar so that you can lift it back to the starting position. Yes this is slow and tedious but you will be thankful for the rest. If you can round up 2 spotters they can stand at either end of the bar and lift it back up for you.

Single Limb Eccentrics – These work best when using a machine such as a leg press. Use one leg/arm during the eccentric portion, then use both limbs to return it to the starting position.

Eccentrics Plus Over-speed Training

One of the arguments against eccentric training for athletic performance is that if you train “slow” you will be slow. But a recent study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning (Cook et al, 2013) made an interesting discovery. Eccentric training with over-speed stimuli was more effective than traditional resistance training in increasing peak power in a countermovement jump. Eccentric training induced no beneficial training response in maximal running speed; however, the addition of over-speed exercises salvaged this relatively negative effect when compared with eccentric training alone.

What does this mean for you? It means that if it is important to include over-speed training with eccentric training, especially if speed is vital to your sport. The following video by Armour Building, shows you three different ways you can use kettlebell swings for over-speed eccentric training. The first is a traditional KB Swing, but you accelerate the bell back toward your body instead of just letting it float. The second technique involves using a band to do the acceleration back into your body for you. The third and final technique uses a partner who pushes the bell back down when you reach the top of your swing.

Video: Over-Speed Eccentrics With Kettlebell by Armour Building

Bands are very helpful in achieving the over-speed effect with both traditional barbell and body weight exercises. Keep in mind that with bands you may be accelerating a heavy object in the direction of your body so having a spotter for weighted exercises is a smart idea.

Another technique is downhill running or bounding. The act of running or jumping downhill functions in a similar way to depth jumps. You are using the increased landing forces provided by gravity to slightly overload the eccentric portion of the jump (or stride). It is important to find a gentle downhill slope so that you can maintain proper form and stride length throughout.

Using Eccentric Training and Avoiding Injury

As mentioned earlier, eccentric training is extremely taxing on the body and should not be overdone. Be mindful of your rest periods and recovery days. This will help to prevent injury and overtraining. Keep your eccentric lifts to only a couple of exercises per workout. If your goal is athletic performance you should stick to compound movements only.

Plyometric and over-speed training in particular are easy to overdo. Remember that you only need 1-2 days per week of this type of training to achieve results. Ensuring sufficient recovery time is extremely important to maximize performance gains. If you cut this short you are not giving your muscles adequate time to recover and adapt. Without adaption there is no improvement.

In-season athletes should not begin eccentric training until after the playing season. It is best to begin to develop your eccentric base during the off-season. A 2-6 week mesocycle prior to your competition period is the ideal time to focus on maximizing eccentric performance. Once you begin competing it is best to lay-off any heavy eccentrics and focus on 1-2 plyometric and/or <1RM eccentric lifts per training session.

As if improving your performance wasn’t enough, eccentric training may also be beneficial for both injury prevention (Pererson et al, 2011) as well as injury rehab (Lorenz & Reiman, 2011). A number of sports injuries occur when you are unable to decelerate your body properly. You see a lot of non-contact injuries, especially to the knee that could be prevented if you were better able to decelerate your body when landing or changing direction.

Recap

- The ability to develop more force in less time is what makes you a great athlete.

- Being able to store additional force eccentrically allows you to generate additional force concentrically.

- Training the counter-movement leads to a faster, more explosive action.

- Plyometrics can be used for eccentric training and are game-changers when done in moderation.

- Tempo squats are a great way to train eccentrically and can replace traditional squats in your current workout.

- Lifting eccentrically at >1RM can improve your strength and size, but should be done only by advanced lifters and those with spotters present.

- Eccentric training paired with over-speed training will prevent you from losing speed and increase your power output.

- Injury prevention is another benefit of training eccentrics, but be careful incorporating these if you are currently an in-season athlete. The off-season is the time to change up your program.

Micah Faas CSCS

Micahfaas@gmail.com

References:

Cook, C., Beaven, C., & Kilduff, L. (2013). Three Weeks of Eccentric Training Combined With Overspeed Exercises Enhances Power and Running Speed Performance Gains in Trained Athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 1280-1286. Retrieved December 5, 2014, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22820207

Dietz, C., & Peterson, B. (2012). Triphasic training: A systematic approach to elite speed and explosive strength performance. Hudson, WI: Bye Dietz Sport Enterprise.

Farthing, J., & Chilibeck, P. (2003). The Effects Of Eccentric And Concentric Training At Different Velocities On Muscle Hypertrophy. European Journal of Applied Physiology,578-586. Retrieved December 5, 2014, from

Fleck S, Kraemer W. Types of strength training. In: Designing Resistance Training Programs. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2004: 40-43.

Lorenz, D., & Reiman, M. (2011). The Role And Implementation Of Eccentric Training In Athletic Rehabilitation: Tendonopothy, Hamstring Strains, And ACL Reconstruction. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 6(1), 27-44.

Petersen, J., Thorborg, K., Nielsen, M., Budtz-Jorgensen, E., & Holmich, P. (2011). Preventive Effect of Eccentric Training on Acute Hamstring Injuries in Men’s Soccer: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2296-2303. Retrieved December 5, 2014, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21825112

Tesch, P. A., Ekberg, A., Lindquist, D. M. and Trieschmann, J. T. (2004), Muscle hypertrophy following 5-week resistance training using a non-gravity-dependent exercise system. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 180: 89–98. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01225.x